HTML

-

前陆盆地是碰撞造山带的忠实记录者,其盆地演化历史往往能够很好地反映陆陆碰撞及碰撞后的过程[1]。如对现今的特提斯喜马拉雅造山带前陆盆地研究,有效地约束板块的初始碰撞时间、新特提斯洋的闭合以及残留洋的消亡等[2⁃3]。新特提斯洋闭合引起了新生代最为广泛的造山运动事件,形成了世界上最著名的阿尔卑斯—扎格罗斯—喜马拉雅造山带[4]。通过对新特提斯域中的碰撞造山带相关前陆盆地开展研究,分析其沉积和盆地充填历史,有助于了解新特提斯洋的演化过程。

位于新特提斯构造域中段的扎格罗斯造山带,一直以来研究程度较低,基本的地层格架和时空演化还存在争议[5⁃8],使得该地区一些重要地质问题不是很清楚,比如阿拉伯—欧亚板块的碰撞时间、新特提斯洋在扎格罗斯地区的海退时间和过程等[9⁃15]。扎格罗斯前陆盆地自中生代以来发育了巨厚(厚度大于10 km)沉积地层[5,16⁃17],其中,中新世地层包括海相灰岩到碎屑岩沉积[5,18⁃19],可能记录了新特提斯洋在本区的最终消亡和阿拉伯—欧亚板块碰撞后的构造演化过程。碎屑物质沉积主要受控于区域构造影响,扎格罗斯前陆盆地的中新世沉积物质与区域隆升的褶皱冲断带关系密切,记录了扎格罗斯的陆陆碰撞、抬升和剥蚀历史,因此是该时段沉积演化的直接证据。

对于扎格罗斯前陆盆地中新统地层,前人已做了一定的地层学、物源以及沉积演化等方面的工作。前人根据生物地层和磁性地层学研究,认为扎格罗斯Lurestan地区Agha Jari组的形成时间介于13.8~12.3 Ma[18,20]。Pirouz et al.[19]提出新特提斯洋在Khuzestan、Fars地区的穿时海退发生于西部的14~12 Ma至东部的8~1 Ma。Alavi[5]提出扎格罗斯地区中新世发育向上变浅的海退沉积,Gachsaran组蒸发岩在扎格罗斯地区普遍发育[21],Mishan组碳酸盐岩主要沉积于Khuzestan和Fars地区[19],最终被上覆Agha Jari组砂岩和Bakhtiyari组砾岩覆盖[18⁃19]。Zhang et al.[6]利用碎屑锆石年龄研究前陆盆地的物源,认为早中新世沉积物源主要来自蛇绿岩带和伊朗南部岩浆弧带,中晚中新世地层物源来自Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带。李佳纬等[22]利用磷灰石(U-Th)/He年龄得出Khuzestan地区Agha Jari组物源来自扎格罗斯蛇绿岩带、Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带和高扎格罗斯带。总体上,记录新特提斯洋关闭的中新世沉积演化以及区域对比研究在扎格罗斯地区还很薄弱。

通过对伊朗南部Lurestan和Khuzestan两个地区的扎格罗斯前陆盆地中新统Agha Jari组开展野外工作,对其进行详细的地层学、沉积学、岩石学和碎屑锆石U-Pb年代学等研究,并通过区域对比,恢复了伊朗南部扎格罗斯造山带的中新世碎屑沉积过程与物源供应,进而为新特提斯洋在该地区的演化提供新的约束。

-

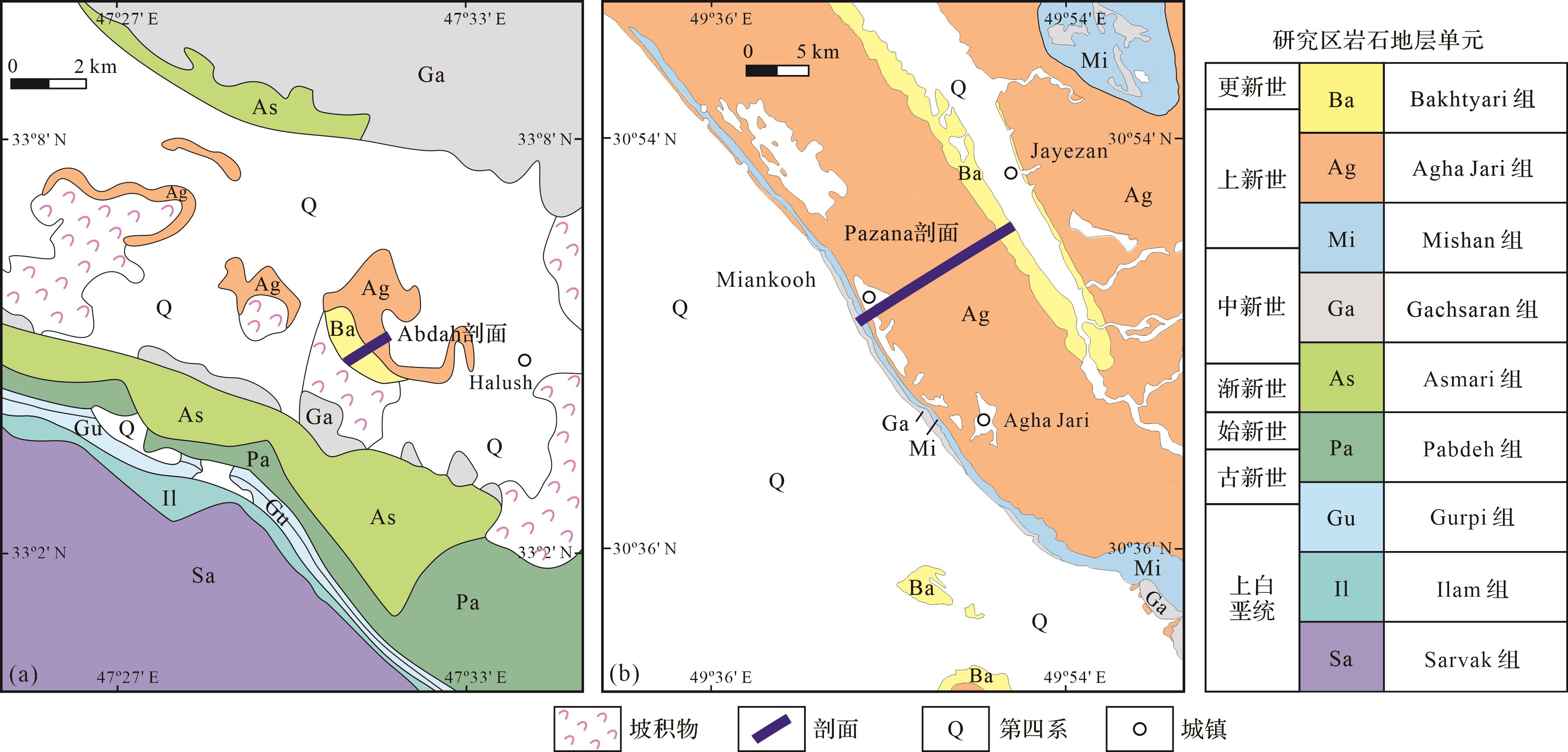

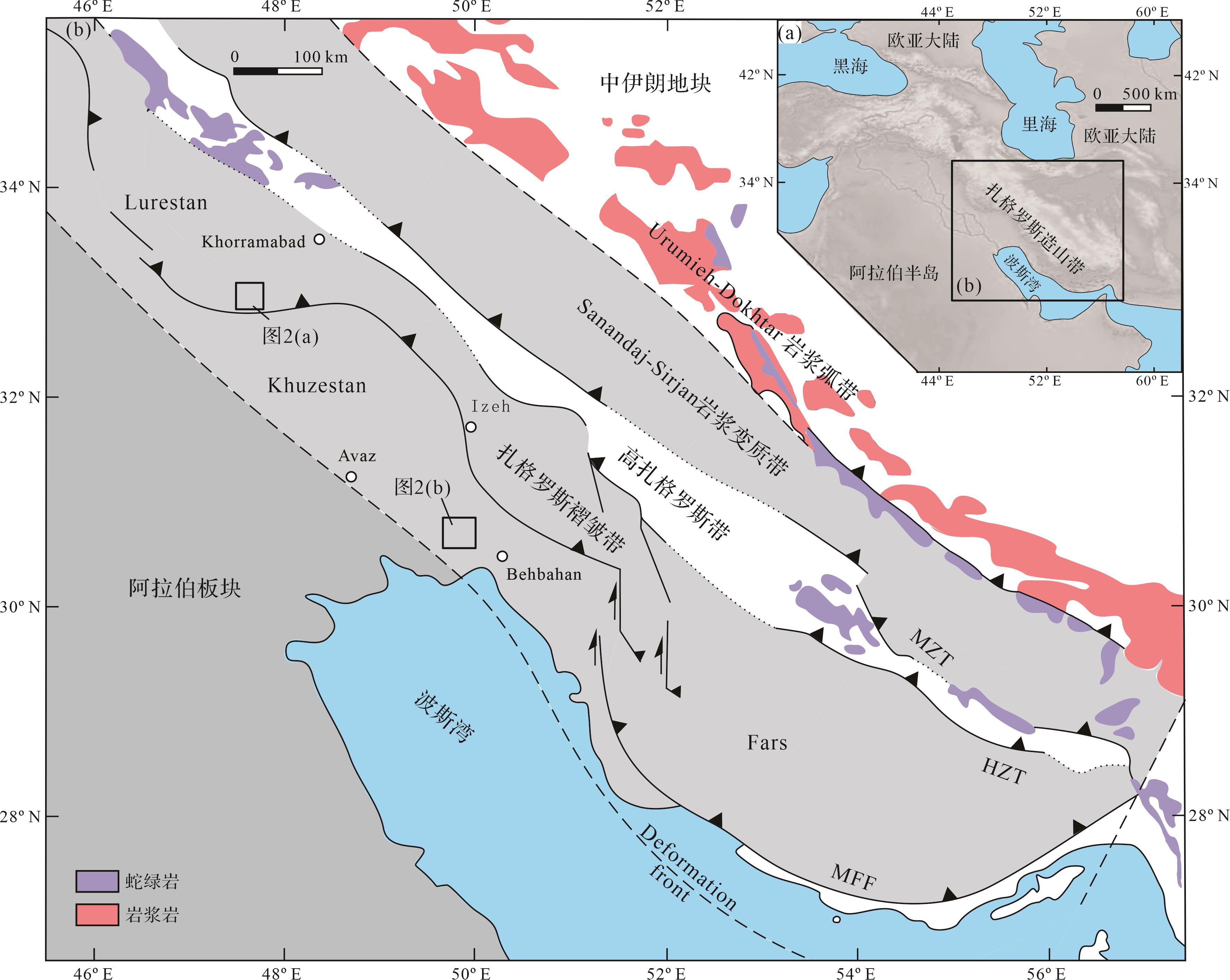

扎格罗斯造山带由自北向南三个构造单元组成,分别为Urumieh-Dokhtar岩浆弧、Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带和扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带(Zagros Fold-and-Thrust Belt)(图1)[23⁃25]。

Figure 1. Geological map of the Zagros region (modified from reference [25])

Urumieh-Dokhtar岩浆弧位于Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带的东北侧,呈北西—南东走向与扎格罗斯山脉相互平行,其形成可能与新特提斯洋壳俯冲及伊朗—阿拉伯板块碰撞相关[26⁃28]。该岩浆岩带以钙碱性火成岩为主,活动时间主要为始新世至渐新世晚期(55~25 Ma),其次为岩浆活动逐渐减弱的中新世(22~6 Ma)[28⁃29]。

Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带位于扎格罗斯主逆冲断层北侧,宽150~200 km,长约1 500 km。该地区以钙碱性侵入岩、喷出岩及变质岩为主[23,30],前人对该地区岩浆岩形成时间约束为侏罗纪(180~144 Ma)时期[31⁃33],其形成与新特提斯洋壳的北向俯冲或晚期的阿拉伯—欧亚大陆碰撞相关[34⁃36],随后在始新世晚期(40~34 Ma)岩浆作用再次活动[36⁃37]。该带变质岩主要由侏罗纪高压低温相蓝片岩组成[23,38]。

扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带可分为高扎格罗斯带(High Zagros Belt)和扎格罗斯褶皱带(Simply Folded Belt)[23⁃24](图1)。高扎格罗斯带位于扎格罗斯主逆冲断层南侧,该区发育由大量薄皮状变形的褶皱和断层,是扎格罗斯地区造山活动最强烈区域。该区地层主要以叠瓦状构造的硅质岩—蛇绿岩杂岩体岩片、中生代—新生代沉积岩组成[24]。区域内出露两套典型蛇绿岩,分别是西北侧的克尔曼沙赫蛇绿岩和东南侧的内里兹蛇绿岩,两者年龄分别为85±6 Ma[39⁃41]和90±15 Ma[34,42⁃43]。

扎格罗斯褶皱带位于阿拉伯板块前缘,临近波斯湾地区,整体以扎格罗斯山前断层(MFF)和高扎格罗斯断层(HZF)为边界与其他构造单元分开。该带自西北向东南分布于Lurestan、Khuzestan和Fars地区,发育大量褶皱和断层,地势呈现朝北东方向逐渐增高趋势[5,44⁃45]。扎格罗斯褶皱带新元古代至新生代的沉积物厚度超过13 km,其中在新元古代至白垩纪发育被动陆缘沉积,晚白垩世之后发育前陆盆地沉积。Lurestan地区是扎格罗斯地区造山过程中主要的隆升区域,构造带内褶皱发育、断层活跃。在渐新世之前研究区内沉积了一系列的海相碎屑岩和碳酸盐岩,随着前陆盆地沉积环境演化,在中新世之后发育Gachsaran-Mishan组浅海蒸发岩和碳酸盐岩,随后被Agha Jari组砂—泥岩和Bakhtiyari组砾岩覆盖[5]。Khuzestan地区是与Lurestan地区相邻的沉积构造带,在中新世之后相继沉积了Gachsaran组、Mishan组、Agha Jari组和Bakhtiyari组[21]。

-

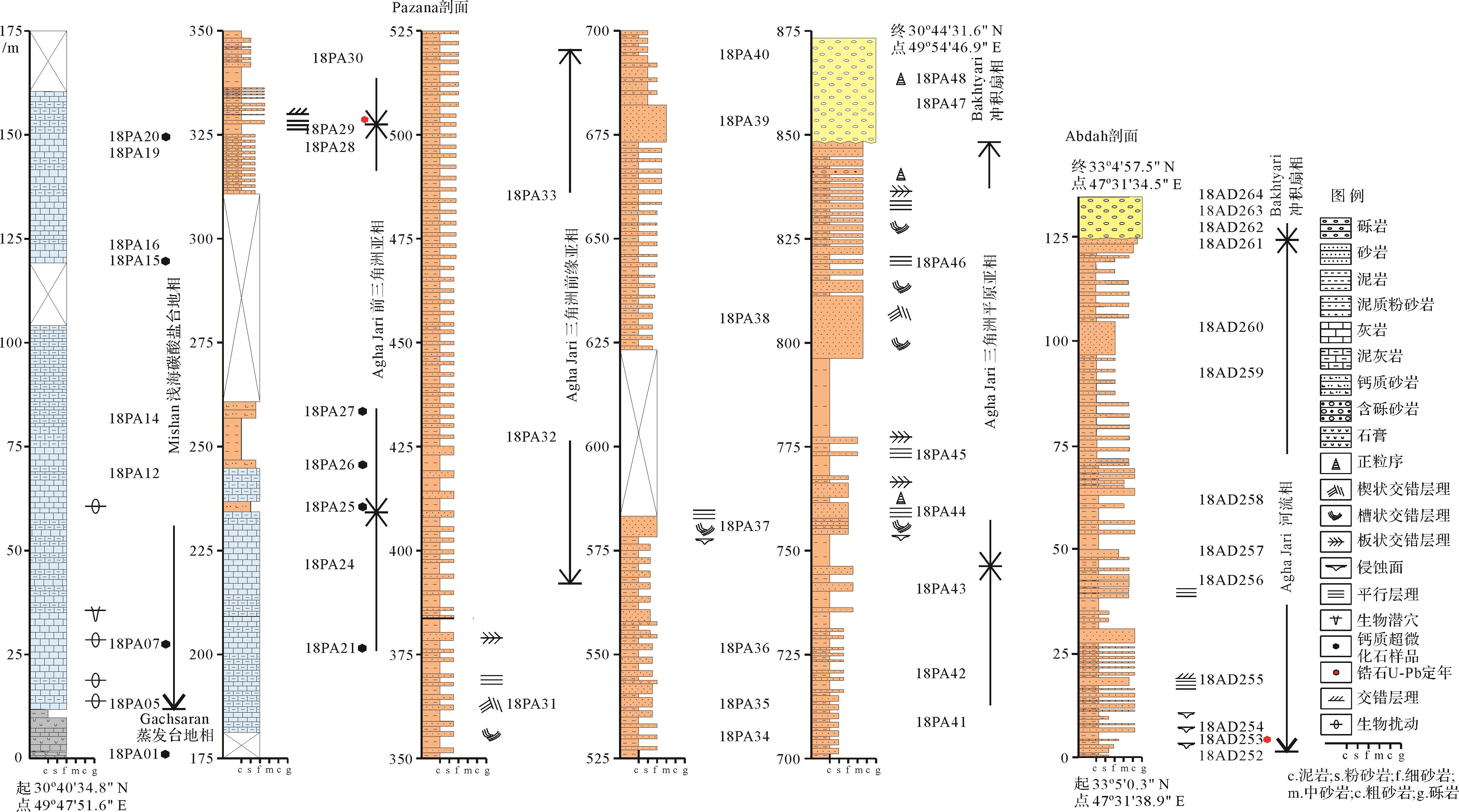

本次工作对伊朗南部Lurestan地区和Khuzestan地区两个剖面的中新统Agha Jari组进行了详细的野外和室内分析研究(图2)。

-

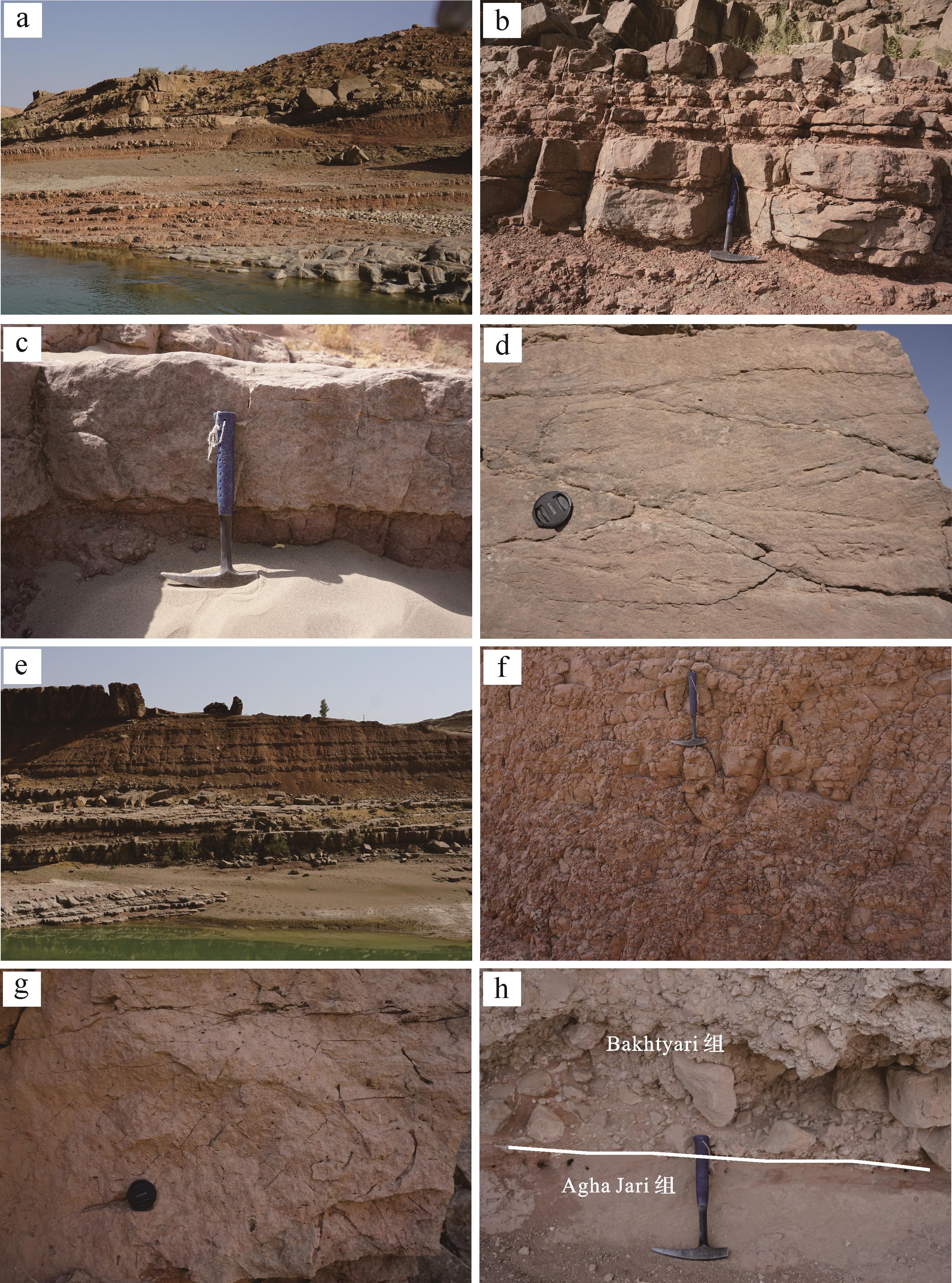

Lurestan地区Abdah剖面出露Agha Jari组和Bakhtiyari组两套地层(图3、图4a),未见底。下部Agha Jari组厚约125 m,主要由紫红色、灰白色粉—中粗粒砂岩和紫红色泥岩组成,顶部以粗粒砂岩为主。沉积构造发育,如冲刷侵蚀面、平行层理和板状、楔状交错层理等。该剖面可见多个砂—泥岩旋回结构(图4b),单个旋回厚2~4 m,呈向上逐渐变细的正旋回。砂岩层底部通常发育冲刷侵蚀构造(图4c),以中粗粒砂岩为主,部分含砾石。砂岩层中发育大量高角度板状(图4d)、楔状和槽状交错层理和平行层理。砂岩之上逐渐过渡到泥岩—粉砂—细砂岩沉积,厚度相比下伏砂岩层较薄(一般介于10~50 cm,图4e),其中粉砂岩呈薄层状、透镜状产出,侧向不连续,层内发育小型交错层理。部分砂—泥岩旋回中,泥岩层厚度较大(大于2 m),以紫红色泥岩为主(图4f),内部可见植物根管和生物钻孔等遗迹构造(图4g),局部可见水平层理发育。

不整合覆盖于Agha Jari组之上的Bakhtiyari组(图4h),单层厚度大于20 m,是一套巨厚层灰白色灰质砾岩层,砾岩层砾石分选性较差,粒径介于0.5~80 cm,砾石磨圆度中等,磨圆度为次棱角状—次圆状,但分选较差,最大砾石粒径超过20 cm,最小可至厘米级(图4h)。砾岩层整体呈颗粒支撑,粗粒砂岩基质常见,砾石排列混杂,呈块状构造。

-

Agha Jari组中大量出现的粗粒含砾砂岩层反映较强水动力的底负载推移质搬运过程,分析其属于曲流河河道沉积单元中的河床滞留沉积[46]。大量槽状和板状交错层理发育的砂岩层显示强水动力侧向迁移的搬运沉积特征,对应于河道中的边滩沉积单元。薄层泥岩—粉砂—细砂岩组合单元,层内发育小型交错层理,反映水动力较弱的特征,其可能形成于河流环境中的堤岸沉积,较粗粒度的粉砂—细砂沉积可能形成于天然堤中的决口扇沉积微相。大套紫红色厚度块状泥岩,局部含水平层理,反映弱水动力环境,推测其形成于河流环境中的洪泛平原沉积单元。Bakhtiyari组大套砾岩层中局部可见粗砂岩透镜体,该套混杂的砾岩沉积反映快速堆积特征,指示高密度碎屑流沉积,推测其形成于冲积扇环境[47]。

综上,通过Abdah剖面的沉积特征分析,该剖面Agha Jari组应形成于曲流河相环境,其上被Bakhtiyari组冲积扇不整合覆盖。

-

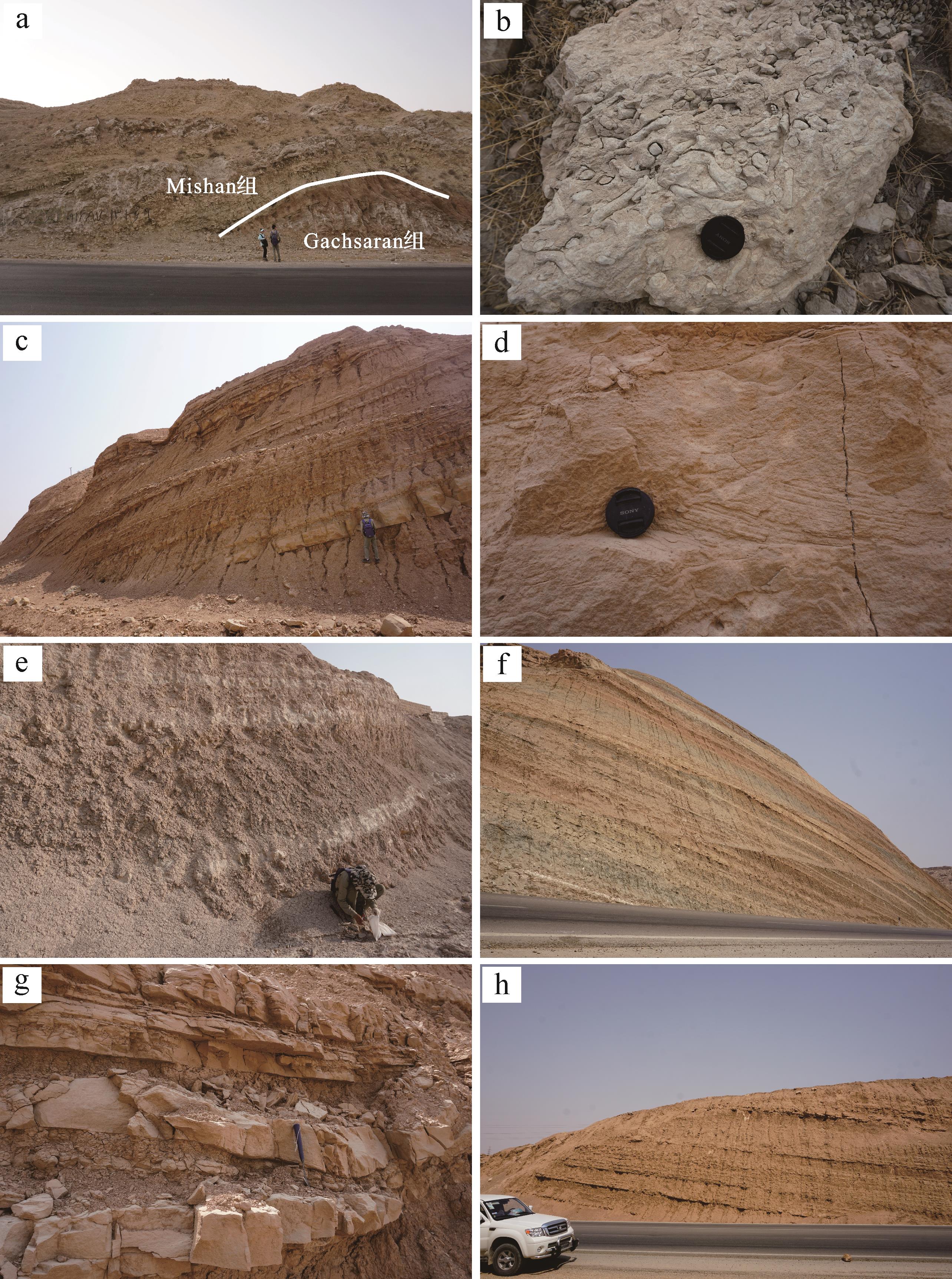

Khuzestan地区Pazana剖面在野外展布为一背斜,自核部向两翼包含四套岩石地层单元,依次为Gachsaran组、Mishan组、Agha Jari组和Bakhtiyari组(图3)。位于背斜核部的Gachsaran组在研究区出露厚度约12 m,以云质灰岩和泥灰岩夹膏岩层为特征(图5a),部分层中夹灰绿色泥岩和紫红色泥页岩。Mishan组整合覆于Gachsaran组之上,厚约222.5 m,该组底部为厚层灰白色灰岩夹泥灰岩,灰岩中发育生物扰动和潜穴遗迹沉积构造(图5b),向上生物扰动减少,岩性为厚层灰岩夹泥灰岩。

Agha Jari组覆盖于Mishan组之上,厚约614 m,整体呈向上粒度变粗的层序,自下而上大致可分为三段。下段厚约91.5 m,该段主体呈现中—厚层灰黄色—紫红色泥岩层(厚度20 cm~2 m不等),夹薄—中层细砂岩层(厚度不超过20 cm,图5c)。砂岩层底部与泥岩层常呈突变接触,侧向延伸较好,部分呈透镜状或楔状形态,层内发育小型波状交错层理(图5d)。该泥岩岩相中部分层段夹多层灰白色蒸发岩层,以石膏层为主,层厚20~50 cm(图5e)。

中段厚约420.5 m,在剖面中上部广泛发育大套厚层灰黄色—黄绿色细—中粒砂岩相,整体颗粒粒度分选较好,层内发育大量交错层理和平行层理。砂岩层侧向延续性好,层厚稳定,单层厚度超过50 cm,呈席状延伸展布,垂向上体现出不同色调的砂岩层相间产出(图5f),显示出延伸不同的结构砂岩纹层出现。部分砂岩层中夹杂薄层状、楔状泥岩层,层厚小于20 cm,层内发育小型波状交错层,局部可见蒸发岩夹层。

上段厚约102 m,以紫红色中层中—粗粒砂岩与粉砂岩、泥岩互层产出(图5g),单套旋回厚约2 m,砂—泥岩层厚比约1∶1。砂岩层下部常常具有冲刷—充填构造或侵蚀的底边界,部分含有砾石成分,向上粒度逐渐变细,呈现正粒序。层内发育中—大型交错层理、平行层理等,泥岩层总体呈块状构造,偶含植物碎片。厚层紫红色—灰黄色泥岩层(总厚度超过100 m,图5h),主要出现于剖面的中上部,平均单层泥岩厚度约5 m,侧向延伸稳定,只在局部夹薄层粉砂岩层(厚度小于10 cm),沉积构造少见,以水平层理为主。

剖面最顶部Bakhtiyari组在本剖面出露总厚度超过25 m,底部以大套砾岩层与下伏Agha Jari组呈角度不整合接触。砾岩主要为颗粒支撑结构,磨圆度较好,多为次圆—圆状,分选差,粒径介于0.5~15 cm,砾岩层可见交错层理发育,侧向多呈楔状或透镜状产出,可见叠瓦状排布的砾石。

-

Pazana剖面中Gachsaran组大量出现的白云质灰岩和蒸发岩反映了气候干燥的局限海或封闭浅海环境,如潟湖相。其上整合接触出现的Mishan组以厚层灰岩夹泥灰岩为主,反映浅海碳酸盐岩台地沉积环境。

Agha Jari组下段以中—厚层泥岩层为主体,指示其形成于水动力较弱的环境,综合垂向层序推测其可能为三角洲前缘的支流间湾微相。泥岩中夹的薄层和透镜状细砂岩层,发育小型交错层理和冲刷—充填构造,对应于三角洲前缘中的远沙坝沉积。中段以大套厚层席状砂岩为特征,呈现较好的分选性,代表其受到反复的波浪淘洗和簸选作用,推测其属于三角洲前缘的席状砂。砂岩层中夹杂的薄层泥岩层,偶夹蒸发岩层,为弱水动力条件下与海局限相通的低洼海湾区,可能为前三角洲泥或支流间湾微相下形成的泥楔沉积单元。上段出现大套砂—泥岩互层组合,砂岩层底部为含砾中粗粒砂岩,并以正粒序为特征,反映牵引流下的床沙推移搬运堆积,结合垂向沉积特征,指示其形成于三角洲平原亚相的分支河道微相。与砂岩互层的紫红色粉砂岩、泥岩,反映了水动力较弱的悬浮沉积搬运特征,结合垂向岩相分布特征,表明其形成于三角洲平原上的天然堤和沼泽微相。本段中上部出现大套厚层泥岩相,指示形成于低水动力条件,其可能形成于三角洲平原上的泛滥平原环境。

与Abdah剖面类似,Pazana剖面顶部的Bakhtiyari组砾岩同样反映快速堆积特征,其形成于高密度碎屑流的沉积背景,即为冲积扇环境[47]。

综合以上野外特征分析,在Pazana剖面,其底部以浅海相碳酸盐沉积为特征,向上逐渐过渡到Agha Jari组以海陆过渡相的三角洲环境,最后被冲积扇相的Bakhtiyari组不整合覆盖。

-

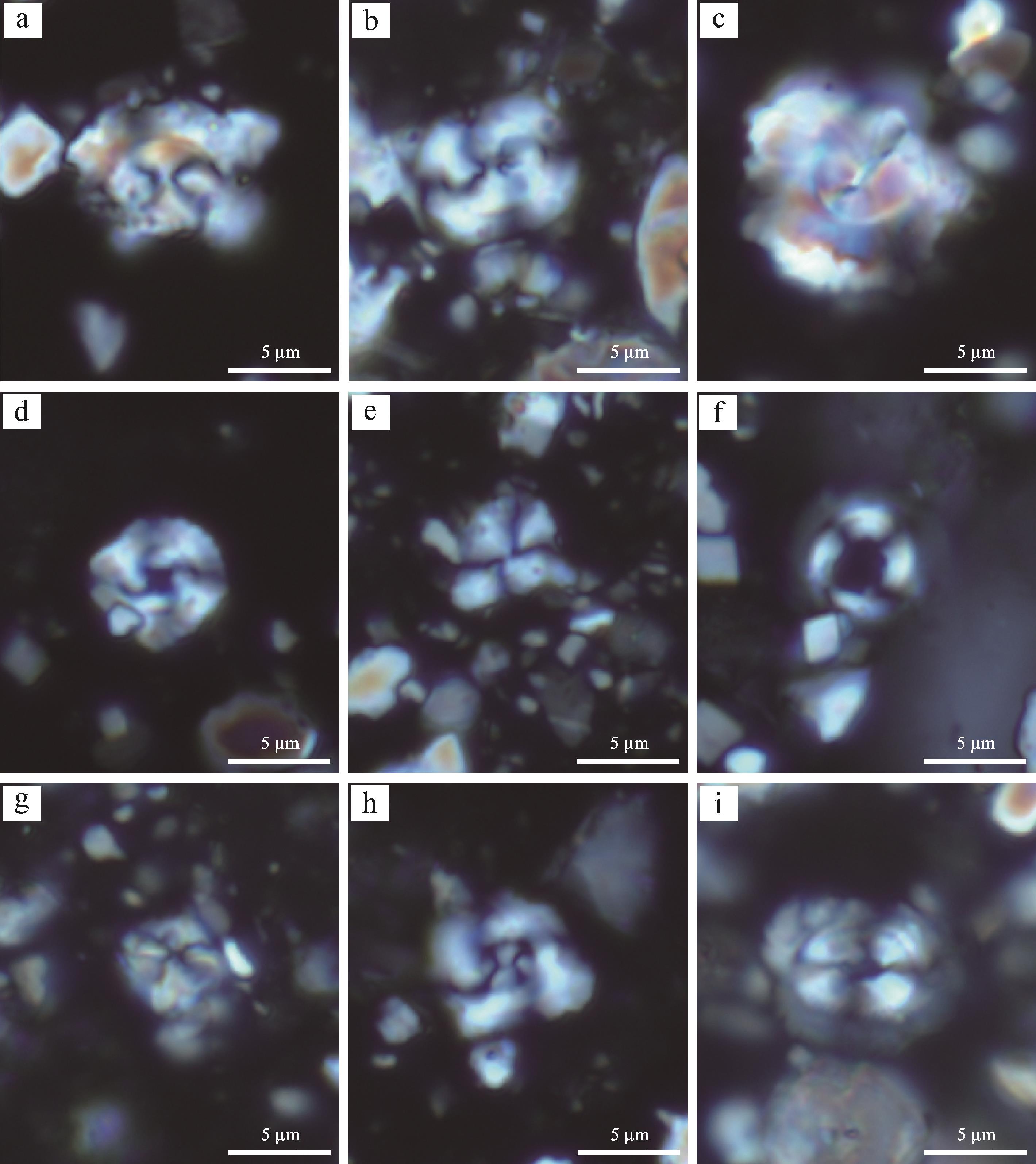

由于Agha Jari组主体形成于陆相或海陆过渡相地层,生物化石保存较少,使其形成时代一直难以约束。前人的研究主要是通过对下伏Mishan组灰岩来限定其下限时代。从Mishan组顶部的双壳化石(Corbula tunicosulcata Vredenburg、Dosinia peralta Vredenburg、Anadara sp.及Thracia sp.)分析,将Mishan组的沉积时代约束于16.0~11.6 Ma[48]。此次研究在Panaza剖面获得下伏地层Mishan组的钙质超微化石,种属包括Cyclicargolithus floridanus、Watznaueria barnesiae、Coccolithus formosus、Micula sp.、Reticulofen⁃ estra reticulate和Coccolithus pelagicus等(图6),其中带化石Reticulofenestra bisecta属于NP25生物带,指示Mishan组沉积至少可以延续至中新世最早期(~23 Ma)。综合前人对Mishan组的生物地层研究,认为Agha Jari组主体沉积于中新世时期。

2.1. Lurestan地区

2.1.1. 沉积地层描述

2.1.2. 沉积环境解释

2.2. Khuzestan地区

2.2.1. 沉积地层描述

2.2.2. 沉积环境解释

2.3. 沉积时代约束

-

砂岩碎屑统计:采用Gazzi-Dickinson栅格结点计数的方法对18个样品进行了碎屑统计[49⁃51]。首先根据砂岩粒径选择合适的栅格间距(一般栅格尺寸大于大部分砂岩颗粒粒径,以确定不会对某颗粒重复计数),然后对每个节点进行识别和统计。统计时,对大于62.5 μm的颗粒进行单独计数,减少砂岩结构成熟度对统计结果的影响。每个样品统计至少300颗碎屑颗粒,统计完成后,通过换算得出各种碎屑的百分含量,用于石英—长石—岩屑(QFL)或其他碎屑组分的三角图解,来反映其构造背景。

碎屑锆石U-Pb年代学:碎屑锆石年龄测定在南京大学内生金属矿床成矿机制研究国家重点实验室完成。所采用仪器为New Wave UP213带固体激光剥蚀系统(LA)的Agilent 7500a型等离子质谱仪(ICP-MS),单个样品点的测试时间为120 s,其中背景测量时间40 s,激光剥蚀分析时间50~80 s。同位素206Pb、207Pb、208Pb、232Th和238U分析停留时间依次为15、30、10、10和15 ms。详细测试方法参考文献[52],获得的数据通过GLITTER版本进行处理[53],并通过普通铅校正[54]。校正后的结果用IsoplotV3.23宏程序完成年龄谱图的绘制[55]。

-

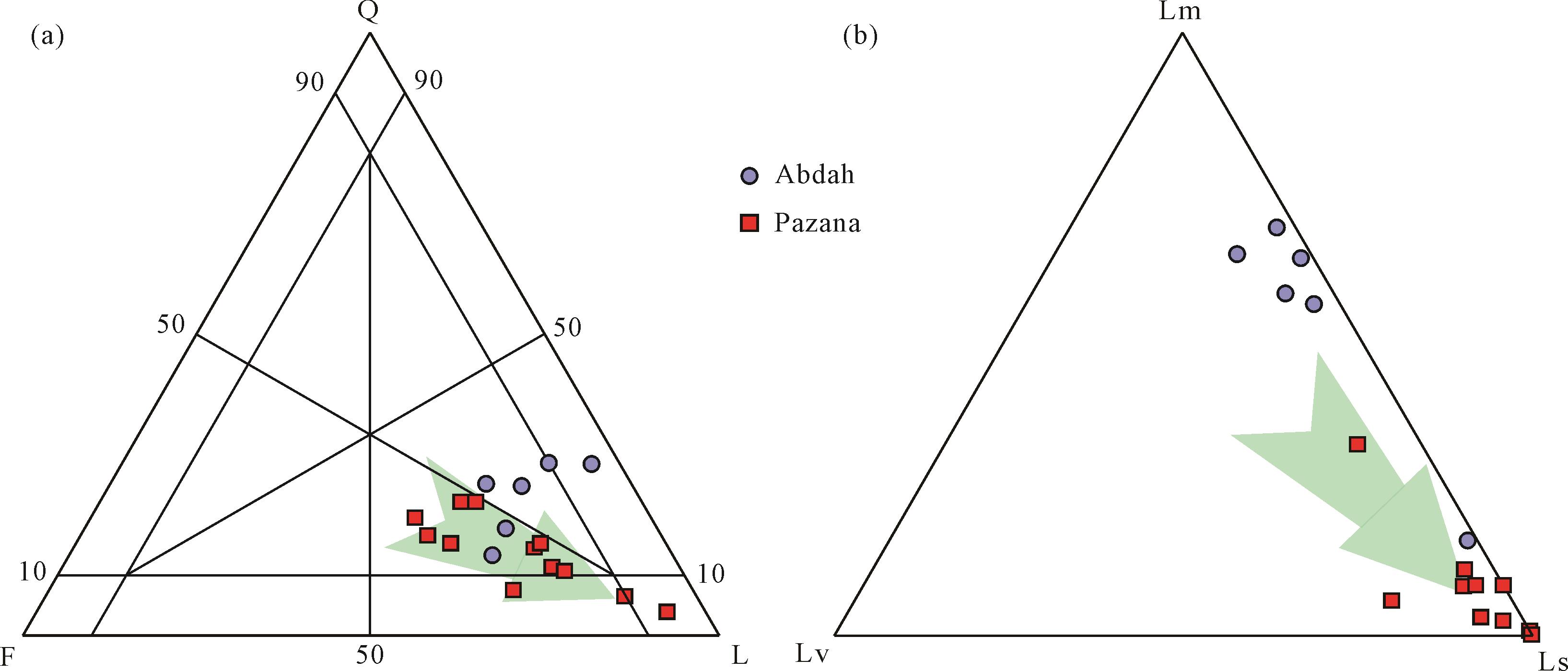

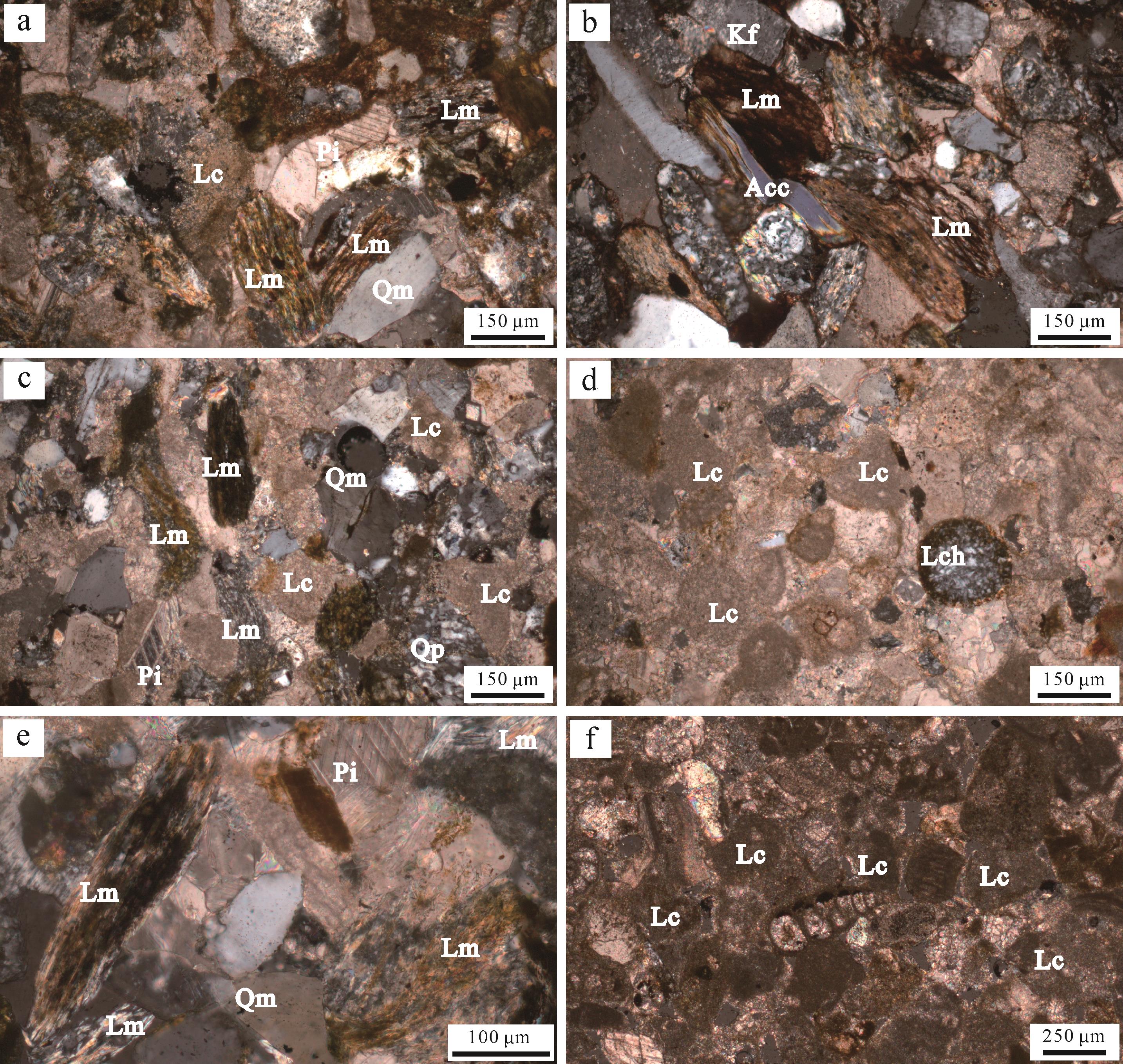

Abdah剖面的Agha Jari组砂岩类型为岩屑砂岩(图7)。碎屑组分统计结果显示平均碎屑组分为Q∶F∶L=22∶18∶59;Lm∶Lv∶Ls=53∶3∶44(表1)。颗粒组成以岩屑为主,石英和长石次之。岩屑含量相对稳定,占比达60%,其组成以变质岩岩屑和沉积岩岩屑为主(图8a,b),且变质岩岩屑含量从岩层底部(~36%)至顶部(~9%)逐渐下降,而沉积岩岩屑含量逐渐升高(从~15%到~43%)。石英含量自底向上呈下降趋势(从~24%到~12%),石英由单晶石英和多晶石英组成,单晶石英含量由岩层底部至顶部变化不大,而多晶石英含量逐渐减少。长石主要包括斜长石和钾长石,总含量在剖面上变化不大(~20%)。

位置 地层 样品号 Qm Qp Pl Kf Lch Lc Lp Lm Lv Acc M 总计 Abdah剖面 Agha Jari组 18AD254 45 48 37 23 0 79 1 141 4 12 5 395 18AD255 37 61 15 20 8 54 1 142 6 14 4 362 18AD258 48 37 34 37 5 58 4 104 13 14 13 367 18AD259 36 10 38 19 1 64 1 88 6 23 24 310 18AD260 27 9 33 37 4 132 1 26 2 24 9 304 Pazana剖面 Agha Jari组 18PA26 53 11 44 68 13 116 4 12 9 18 5 353 18PA27 36 10 40 54 9 128 3 18 7 23 4 332 18PA28 40 16 53 60 4 150 0 5 10 18 23 379 18PA29 24 24 36 28 25 167 3 18 9 13 0 347 18PA31 40 6 33 22 7 197 0 0 0 22 42 369 18PA34 13 16 10 36 11 187 0 1 0 15 19 308 18PA35 42 15 26 41 6 120 1 3 4 29 60 347 18PA37 31 36 26 47 17 80 1 52 15 20 23 348 18PA39 26 7 21 33 15 172 4 17 0 5 76 376 18PA43 14 10 53 30 15 201 0 0 0 1 39 363 18PA44 16 4 18 14 3 250 0 2 0 11 14 332 18PA45 9 4 12 7 19 291 4 0 0 4 17 367 Bakhtiyari组 18PA47 32 10 12 27 6 208 1 7 1 9 21 334 注: Q.石英;Qm.单晶石英;Qp.多晶石英;F.长石;Pl.斜长石;Kf.钾长石;L.岩屑;Lch.燧石;Lc.碳酸盐岩岩屑;Lp.陆源碎屑岩岩屑;Lm.变质岩岩屑;Lv.火山岩岩屑;Acc.副矿物;M.基质。Table 1. Statistical results of sandstones from the Agha Jari Formation

Pazana剖面中,Agha Jari组的砂岩类型同样以岩屑砂岩为主(图7)。碎屑结果显示平均碎屑组分为Q∶F∶L=14∶22∶65;Lm∶Lv∶Ls=5∶2∶93(表1)。碎屑成分自下而上石英和长石含量均呈下降趋势,其中石英从~18%下降到~3%,长石从~31%下降到~5%。岩屑含量自底而上逐渐增多(从~44%到~86%),并以碳酸盐岩沉积岩屑为主(~49%),且向上有增多趋势(从~33%到~79%)。Pazana剖面中的Agha Jari组与Abdah剖面中的相比,砂岩岩屑组分含量差异较为明显,Abdah剖面在沉积早期出现大量变质岩岩屑(图8a,b),随后沉积岩岩屑含量逐渐增多,而Pazana剖面的岩屑始终以碳酸盐岩沉积岩屑为主(图8c~f)。

-

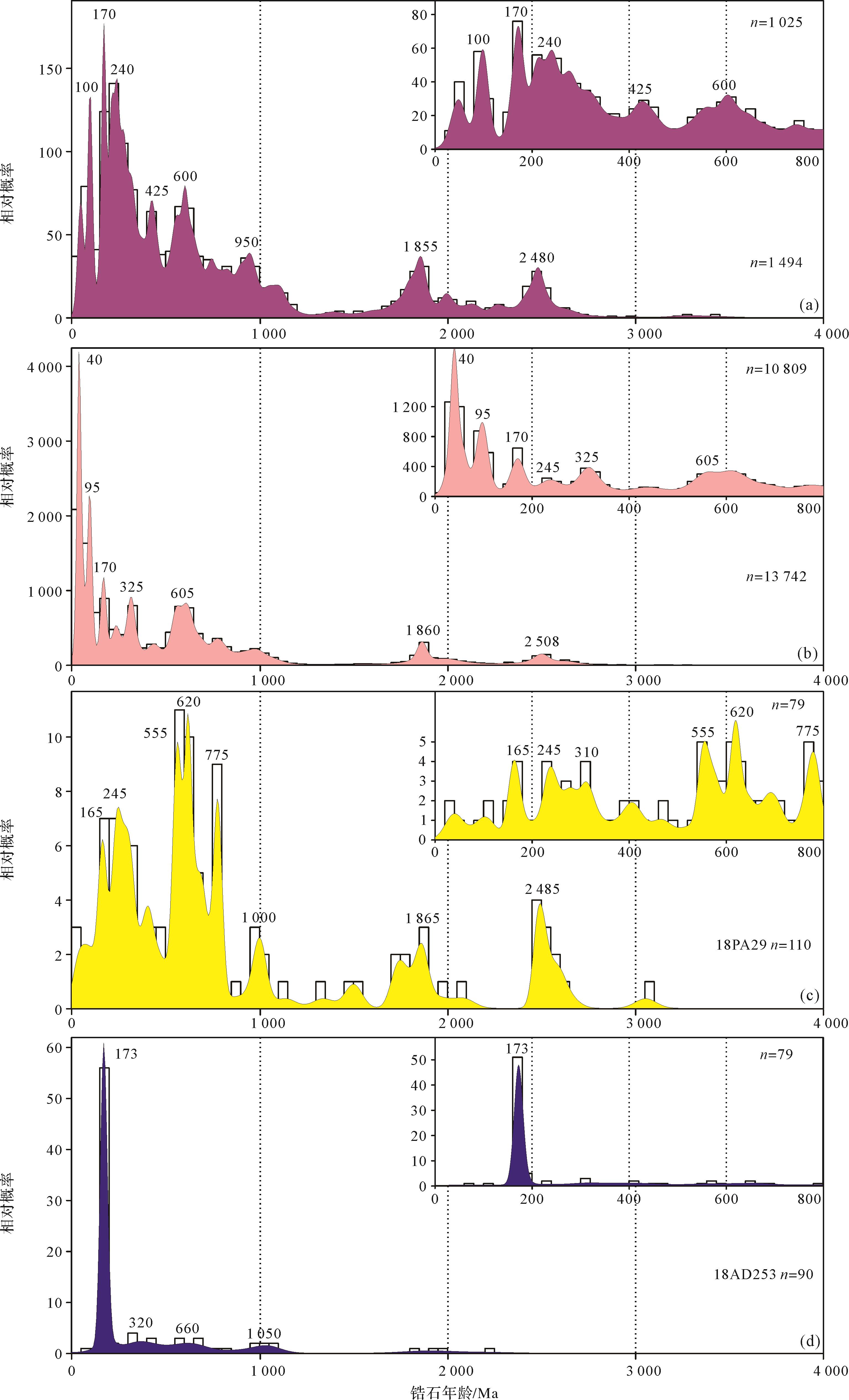

对两件样品200颗碎屑锆石开展锆石U-Pb年代学分析1。Lurestan地区Abdah剖面砂岩样品(18AD253)获得了90颗碎屑锆石年龄(图9),其中56颗(占比62%)显示年龄区间为150~200 Ma,峰值为~173 Ma;其余锆石年龄分别显示200~400 Ma(占比9%,峰值~320 Ma)、500~750 Ma(占比9%,峰值~660 Ma)、900~1 100 Ma(占比7%,峰值~1 050 Ma)。

Figure 9. Comparisons of probability density for detrital zircons from the Agha Jari Formation to the potential source areas

Khuzestan地区Pazana剖面砂岩样品(18PA29)获得了110颗碎屑锆石年龄(图9),结果显示其主要年龄区间为80~110 Ma (占比3%,峰值~100 Ma)、150~180 Ma(占比5%,峰值~165 Ma)、200~350 Ma(占比16%,峰值~245 Ma、~310 Ma)、520~730 Ma(占比27%,峰值~555 Ma、~620 Ma)、750~800 Ma(占比8%,峰值~775 Ma)、950~1 200 Ma(占比5%,峰值~1 000 Ma)、1 700~2 100 Ma(占比9%,峰值~1 865 Ma)、2 450~2 700 Ma(占比9%,峰值~2 485 Ma)。该样品中出现的最年轻碎屑锆石年龄为35±1 Ma。与Abdah剖面相比,该样品出现了大量的白垩纪锆石年龄(图9)。

3.1. 物源分析方法

3.2. 分析结果

3.2.1. 砂岩碎屑组分

3.2.2. 碎屑锆石U⁃Pb年龄

-

通过搜集潜在物源区的碎屑锆石年龄与Agha Jari组进行对比,并结合砂岩的碎屑组分特征来限定物质源区。位于扎格罗斯主逆冲断层北侧的Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带出露大量中—新生代沉积地层和变质岩,其分散的碎屑锆石年龄区间显示最主要特征年龄峰区间为160~200 Ma[75](峰值为~170 Ma,图9)。位于扎格罗斯主逆冲断层南侧的扎格罗斯前陆盆地沉积厚度巨大,发育数十千米沉积地层,碎屑锆石年龄显示其两个主要年龄峰值区间,即20~65 Ma(峰值~ 40 Ma)和80~110 Ma(峰值~95 Ma),其他年龄峰值包括~170 Ma,~245 Ma,~325 Ma,~605 Ma和~1 860 Ma[56,63⁃75](图9)。

对比Agha Jari组碎屑锆石年龄发现,Lurestan地区Agha Jari组砂岩样品广泛出现侏罗纪150~200 Ma年龄峰值,这与北侧Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带中锆石年龄特征相似[56⁃62](图9),碎屑组分分析表明,Lurestan地区砂岩碎屑组分含有大量变质岩岩屑,这同样指示北侧Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带是其最可能的物质来源。相比于Lurestan地区,Khuzestan地区砂岩碎屑锆石年龄特征与之有一定的不同,除出现区域特征性的泛非期锆石年龄外(500~1 000 Ma),其特征的年龄峰值包括中生代245 Ma、165 Ma和100 Ma,尤其是白垩纪锆石年龄(峰值~100 Ma)在该地区出现。通过对比,这些中生代锆石与扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带中的碎屑锆石年龄相似(图9),同时对比该地区砂岩样品中出现大量的沉积岩岩屑,表明其物质很可能再旋回自扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带内大量的中—新生代碳酸盐岩。

综上,研究区内两条剖面中的Agha Jari组沉积物源有一定的差别。位于扎格罗斯造山带西北侧Lurestan地区的Agha Jari组,碎屑物质主要来自紧邻剖面北侧的Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带,而位于扎格罗斯造山带东南侧Khuzestan地区的碎屑物质主要是再旋回自早先沉积于扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带内的沉积地层。

-

研究区沉积地层分析表明,扎格罗斯地区在渐新世—早中新世时期处于Gachsaran组蒸发岩沉积的台地环境[21],以膏岩地层为特征。随后区域海平面开始上升[19,48],使得扎格罗斯东南部地区发生海侵,沉积环境由蒸发台地变为浅海开放碳酸盐台地,形成了Mishan组浅海灰岩沉积。

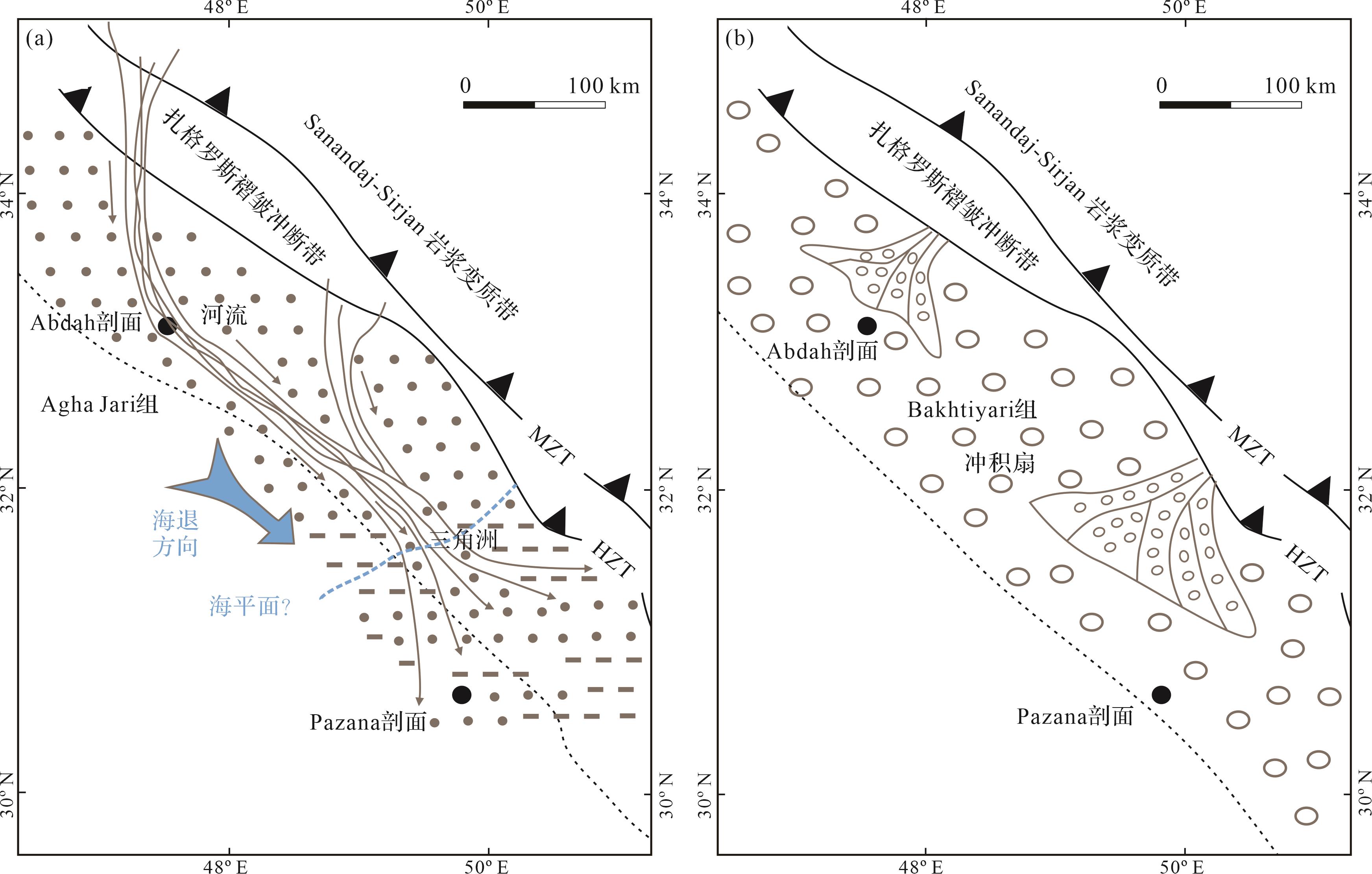

随着海侵结束,Mishan组碳酸盐岩停止沉积,区域受到扎格罗斯褶皱冲断构造影响,该地区海水逐渐退出[18⁃20]。此时,扎格罗斯造山带西北部Lurestan地区,Agha Jari组形成于河流环境,而东南部的Khuzestan地区,沉积于浅水碳酸盐岩台地Mishan组之上的Agha Jari组,形成于海陆过渡环境的三角洲相(图10a)。该时期,扎格罗斯地区为自西北的陆相环境至东南的过渡相的三角洲环境,因而,Agha Jari组代表研究区东南侧最晚的海相沉积地层,其演化反映了新特提斯洋在本区域的消亡过程。从沉积古地理可以发现新特提斯洋的消亡过程从西北自东南存在穿时现象(图10a),并基于Agha Jari组的形成时代,推测新特提斯洋在扎格罗斯地区的最终消亡时间为中新世初期。Agha Jari组沉积之后,区域内从河流—三角洲过渡环境转变为陆相冲积扇环境的Bakhtiyari组沉积,形成大套粗粒砂—砾岩沉积(图10b),两者之间以区域广泛存在的不整合为界[44,76],代表了整个扎格罗斯地区继续发生大幅构造隆升和沉积间断。

碎屑岩作为受区域构造背景控制所形成的盆地沉积物,能够记录早期盆地周缘造山带的隆升剥蚀以及与周围环境相互作用的信息[77]。扎格罗斯前陆盆地的沉积充填与造山带的褶皱冲断过程密切相关。中新世之前,扎格罗斯地区以浅海碳酸盐岩和蒸发岩沉积为主[5]。随着阿拉伯—伊朗板块的持续碰撞,陆陆构造挤压变形强烈[23],扎格罗斯造山带逐渐构造抬升,新特提斯洋自西北向东南方向逐渐退出,形成研究区中新世碎屑沉积,Agha Jari组自西北向东南发育的河流—三角洲沉积体系(图10a),在沉积来源上体现了从早期的研究区北侧Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带过渡到后期大量的扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带的物质供应变化,反映了扎格罗斯造山带构造隆升的过程。即在Agha Jari组沉积早期(中新世初期),北侧的Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带受到抬升剥蚀成为区域的物质源区,反映出大量变质岩岩屑和中生代的碎屑锆石特征。随着扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带的不断发育,扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带发生构造抬升,继而为Agha Jari组沉积提供物质供应,使得大量再旋回的碳酸盐岩沉积岩屑被搬运至中新统砂岩碎屑沉积中。李佳纬等[22]的磷灰石(U-Th)/He测试分析结果,同样反映扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带的隆升与剥蚀形成大量的碎屑物质,在前陆盆地充填过程中起重要作用。

基于两个沉积剖面对比,扎格罗斯前陆盆地中新统Agha Jari组完整地记录了盆地充填以及新特提斯洋海退过程,显示在研究区存在同期异相特征,反映了海水最早从西北向东南方向逐渐退出,碎屑物质从西北向东南搬运充填,并于中新统Agha Jari组沉积结束后,海水全部退出该区域,最终区域构造隆升形成大规模的冲积扇沉积。

4.1. 碎屑物源

4.2. 古地理演化与新特提斯洋海退

-

(1) 研究区Agha Jari组为一套最早形成于中新世的地层,沉积环境在扎格罗斯造山带西北Lurestan地区为河流环境,在东南Khuzestan地区为三角洲环境。

(2) Agha Jari组的砂岩碎屑组分显示在Lurestan地区出现大量变质岩岩屑,其碎屑锆石特征显示160~200 Ma年龄区间,表明Sanandaj-Sirjan岩浆变质带为主要碎屑物质来源;而位于Khuzestan地区的砂岩碎屑组分以沉积岩岩屑为主,中生代碎屑锆石年龄特征与扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带相似,其物源是来自再旋回的扎格罗斯褶皱冲断带沉积岩。

(3) 阿拉伯—欧亚板块的碰撞作用,促使扎格罗斯造山带的持续构造抬升,剥蚀的碎屑物质不断充填到中新世扎格罗斯前陆盆地,导致该区海水的逐渐退出和新特提斯洋的最终消亡。基于研究区两个剖面的对比,新特提斯洋自西北向东南方向逐渐退出的古地理格局至少在中新世已经形成。

附1_附表1Agha Jari组碎屑锆石年龄测试结果.xlsx

附1_附表1Agha Jari组碎屑锆石年龄测试结果.xlsx

|

|

DownLoad:

DownLoad: